If you spot any typos while reading this, we’d suggest that you keep them to yourself.

While working on some project planning this morning, I pointed out to the small team I was working with that we should be planning at least three times as much time for certain tasks as we were allotting. “There’s even a law that describes this principle”, I said. “It’s called….um….er….”, and then I suddenly realized that since I was doing several other things at the moment, I was probably falling prey to Miller’s Law. But no worries; after some quick Googling, I found it. Hofstadter’s Law states that “It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.” And Hofstadter was a pretty smart dude; he wrote the brilliant and expansive exploration of science, cognition, and systems called Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. At least we think it was brilliant. There’s probably a law that states that “If information is presented cleverly enough, no-one will understand it, but everyone will act like they do”.

In any case, this sent us into a sudden fit of wikiphilia, and before we knew it, we had basically proven Hofstadter’s Law. Or perhaps the somewhat similar Parkinson’s Law, which states that “Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” Not that we were getting any work done, at that point. And that last sentence highlights something interesting I noticed as we shared the cleverly-phrased laws that we were digging up on the web: many of them are recursive in the same way as that sentence was. Here’s a quick roundup, as examples. I’ll get back to the point further below:

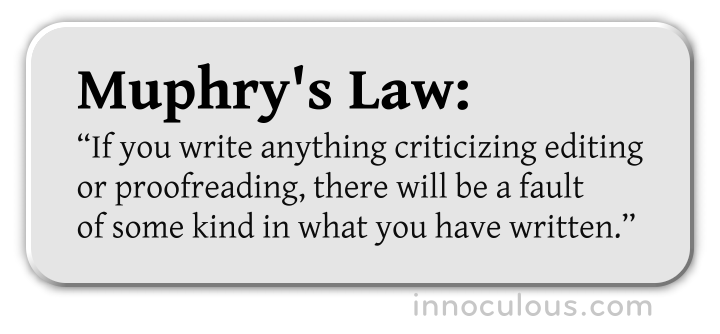

Muphry’s Law

“If you write anything criticizing editing or proofreading, there will be a fault of some kind in what you have written.”

Schneier’s Law

“Any person can invent a security system so clever that she or he can’t think of how to break it.”

Betteridge’s Law of Headlines

“Any headline which ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.”

Hanlon’s Razor

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

Hofstadter’s Law

“It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.”

Poe’s Law

“Without a clear indicator of the author’s intent, parodies of extreme views will be mistaken by some readers for sincere expressions of the parodied views.”

Clarke’s First Law

“If an elderly but distinguished scientist says that something is possible, he is almost certainly right; but if he says that it is impossible, he is very probably wrong.”

Benchley’s Distinction

“There are two types of people: those who divide people into two types, and those who don’t.”

What I noticed was that most of these laws – as amusing and seemingly diverse as they are – rely on a simple recursion, much like a Fumblerule or an antimetabole. If you’re not familiar with those two terms, here are some examples:

Fumblerule

To quote Wikipedia, a fumblerule is “a rule of language or linguistic style, humorously written in such a way that it breaks this rule.”

Examples

- Don’t use no double negatives.

- Eschew obfuscation.

- Prepositions are not words to end a sentence with.

- Avoid clichés like the plague.

- The passive voice should never be employed.

- You should not use a big word when a diminutive one would suffice.

- It is bad to carelessly split infinitives.

- No sentence fragments!

- Parentheses are (almost always) unnecessary.

Antimetabole

If you’re wondering how it’s pronounced, here you go:

The antimetabole has been a device for oration since the time of Socrates, who said “Eat to live, not live to eat.” In modern times, it was employed to effect rather sparingly in the twentieth century, probably the two most notable examples being Churchill and Kennedy’s famous usages:

Winston Churchill:

“Let us preach what we practice—let us practice what we preach.”

John F Kennedy:

“Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

But it came back into vogue in recent years. Whatever your opinion of the man’s politics or personal character, Bill Clinton is arguably one of the most skilled and engaging speakers in contemporary politics, and he revived it in the 1990’s rather masterfully with:

“People the world over have always been more impressed by the power of our example than by the example of our power.”

We’ll never know if the average citizen Barney Smith – who famously uttered the antimetabole below at the 2008 DNC really was an “average citizen”, or a clever DNC plant, but the line is epic:

“We need a president who puts the Barney Smiths before the Smith Barneys.”

This seemed to put some juice back into the trick, in the same campaign, Hillary Clinton delivered:

“In the end the true test is not the speeches a president delivers, it’s whether the president delivers on the speeches.”

John McCain’s writers apparently thought this was clever, and several months later he delivered the zinger:

“We were elected to change Washington, and we let Washington change us.”

Sarah Palin’s people were a little less subtle, using the gimmick literally the next day, with:

“In politics, there are some candidates who use change to promote their careers. And then there are those, like John McCain, who use their careers to promote change.”

This of course is not to be confused with the Russian Reversal, which – although it can be quite funny when interjected into casual conversation as a reference to Yakov Smirnoff’s trademark joke – was only genuinely funny as a standalone remark in its original form:

“In Soviet Russia, TV watches YOU!”